The Story+Data Map: Development & Inspirations

Suggested Citation: Putnins, Susan, Chantal Hoff, and Elizabeth Whitcher. 2025. “The Story+Data Map: Development and Inspirations” Data+Soul, May 16. https://dataplussoul.com/blog/the-story-datamap

The Story+Data Map is a tool for people who want to use data and stories to move towards more equitable, just futures. This tool grew out of our work as evaluators at Data+Soul Research where we strive to work for and with non-profits, community-based organizations, funders, and municipalities using equitable evaluation principles.

We created this tool to make these principles more embedded in our work. The Story+Data Map started off as an alternative to a logic model that is person-centered, uses asset framing, specifies systems challenges, and unites theory of change and data all on one page. It has developed beyond this into a process of bringing multiple voices to the table for not only evaluation but also asset mapping and program design. The people we have used this tool with in the social sector have expressed that it has made these processes more accessible and aligned with their own equity values, and we are now sharing it with a broader audience in hopes that others will feel the same way. We share the tool, its background, and its rationale to give you an even stronger springboard as you develop your own applications.

Our Lineage and Inspirations

We (the authors) are current and former teammates at Data+Soul Research, a research and evaluation consulting firm in Boston, Massachusetts. We practice evaluation with the intentional aim of forwarding social justice and equity to resist the tendency for evaluation to be used as a tool for maintaining the status quo. Below, we share the key theories and tools that have shaped our thinking about equitable evaluation and the power of story and data, and inspired us to develop the Story+Data Map. While we discuss specific thinkers or pieces that shaped our process later on, we would not have had the goals and priorities that brought us to think about the Map in the first place without the inspirations below.

Equitable evaluation: Equitable evaluation means conducting evaluations equitably (Hood, Hopson, & Kirkhart, 2015) and using them to forward equity in the world (Equitable Evaluation Initiative, 2023). We are inspired by the Equitable Evaluation Framework’s invitation to “understand and reimagine how we know what we know,” and the principles it offers to get there by challenging existing orthodoxies in evaluation. D’Ignazio and Klein’s Data Feminism (2020) has sharpened our thinking on power and purported objectivity in evaluation, and We All Count’s (n.d.) Data Equity Framework has guided us on examining equity and power in specific data practices. In our work at Data+Soul, we have synthesized these frameworks into five core principles for working with data in service of equity. These principles are how we bring our team’s commitments to racial and gender equity to action in our day-to-day work:

Humans are more important than data. Data is meant to help humans - not the other way around.

The “how” matters beyond the “what.” Principled processes matter perhaps even more than what they result in.

Complexity and context. Much of the work we evaluate exists within broader systems and contexts, underscoring the importance of nuance rather than simplification.

Shared work + knowledge. Community members are positioned as co-producers of knowledge rather than subjects to be studied.

Multiple truths. The closest we can come to objectivity is by lifting up multiple subjectivities.

Storytelling and data: Data is communicated and made actionable through story. In the words of Terry Marshall and Aisha Shillingford (2017), “our ability to make sense of the world is dependent on narrative.” As people who create and use data, we therefore need to be mindful of how our work contributes to stories about programs and people. Simply put, “the numbers don’t speak for themselves” (D’Ignazio & Klein, 2020, p. 149). This is why Evergreen Data’s (n.d.) Data Visualization Checklist challenges data visualizers to share their takeaways in the title, and storytelling with data encourages data visualizers to think deeply about the story they want to communicate (Knaflic, 2020). In the absence of a purposeful narrative, existing dominant narratives “[where] racism, sexism, and classism make hierarchies, exploitation and violence seem natural and inevitable” (Benjamin, 2024) will be absorbed and repeated. As practitioners committed to equity, this means making sure the narratives we contribute to dismantle rather than to do not replicate the problems we are seeking to solve.

From Logic Model to Story+Data Map: Our Shifts

With equity principles and an acknowledgment of the importance of framing and storytelling with data, how do we actually do this work with communities? The logic model is a hallmark tool of theory-based evaluations (and often required by funders) that is helpful for testing assumptions and differentiating what a program did versus what has changed because of the program (W.K. Kellogg Foundation, 2004; Kidder et al., 2024). However, the model can make it easy to isolate a program’s actions from the systems and contexts that communities move within, despite many encouraging efforts to incorporate it (e.g., Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2004; Meyer et al. 2022). Logic models also start with the program’s resources to contribute to change - not the communities’. With that in mind, we wanted to design a tool that made five key shifts:

From logic to storytelling

As data is never neutral, neither can logic models be. A logic model is often presented as a fact, merely an intellectual exercise to describe objective reality and sound hypotheses. We know that it is actually a kind of story told by a specific set of storytellers who were in the room when it was developed. A workshop on storytelling for social change hosted by Futures Without Violence inspired us early on to reconsider how narrative arcs can be powerful tools to show successes and inspire future action. This led us to think about what the narrative arc of a logic model alternative might be, and inspired us to build the tool off of key elements of a story - protagonists, aspirations, challenges, chosen actions, and outcomes.

Much of the literature (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2004; Meyer et al. 2022) recommends bringing in multiple perspectives when developing a theory of change or logic model. For example, Roman et al. (2025) developed a logic model with young people who have used violence to “enable more participant-centered program refinement and a logic model that truly reflects the priorities of those being served” (p. 8), and Dart & Gates (2024) show how multiple perspectives can lead to “co-creating future possibilities that shift the way people see, experience, and act in the now” (p. 48). However, bringing in community members can often be skipped in practice. We wanted the tool to be explicit about who the storytellers are - with the intention of accountability to bring in multiple perspectives, especially from people who have been resisting systems for generations, but at least with the requirement of naming the subjectivity of the story.

From centering programs to centering people

To change the story from programs serving people to people as protagonists who leverage their strengths to overcome challenges and achieve their aspirations, we have to start by centering the people and communities who (may) choose to participate in a program as a way to support their own journey. We frame the story as individuals or communities choosing to access a program in support of their greater goals, rather than a program finding people to serve. This shift is informed not only by the equity and social justice thinkers from our lineage, but also by approaches that combine human-centered design with evaluation, like design evaluation (Gardner, 2000) and journey mapping (Joseph et al. 2022), that focus on a person moving through a program rather than a program intervening with a person. This further makes success something a program may contribute to, rather than assuming success is fully attributed to the program (or to the funding that supports the program). In the Story+Data map, we wanted to start with the people we are here for and with rather than program inputs as in a logic model.

A shift from centering programs to centering the people they are there for is also an opportunity to recognize that there are often more factors contributing to people reaching their aspirations, beyond the contribution of any single program. And there are many ways to do this in an evaluation besides using the Story+Data Map. For example, Clarke et al. (2022), with the support of a steering committee of local, state, and federal Indigenous representatives, combined elements of a traditional logic model with a medicine wheel to move beyond linear, causal representations and ensure that program logic was embedded within the cultural practices of their communities.

From people’s needs to aspirations and assets

The best stories aren’t about people’s needs; they are about how people use their strengths to overcome challenges in service of a bigger aspiration. It’s common in musical theater that the story truly starts with the main character expressing what they want (Chilla, 2024). This is in line with the asset framing that some of our favorite equity thinkers show are essential for creating narratives that support a just future. Trabian Shorters (2019) describes how deficit-based narratives perpetuate racism and other systems of oppression, while asset framing, which highlights the aspirations and contributions of all people, can disrupt oppression. Na’ilah Nasir (2021) highlights how focusing on equity as an end can mean making people fit fairly into inequitable systems, while focusing on strengths makes it easier to reimagine and remake those systems. Therefore, we wanted to develop a tool that describes communities’ aspirations and strengths rather than needs. This also shifts outcomes from what a program has delivered to how a program contributes to people’s aspirations.

From naming context to positioning systems challenges

Focusing on needs makes failure and the need to change personal; focusing on assets places the locus of responsibility on systems and makes a case for systems change. A parallel requirement for the tool we were developing was then to explicitly position system challenges as standing in the way of individuals’ and communities’ aspirations. Oftentimes logic models have an assumptions or context section as one workaround for embedding the program more in communities’ contexts. For example, Meyer et al. (2022) argue that it is essential to contextualize program theory within systems challenges, and for programs to address both individuals and systems in their work. In other words, program staff risk exacerbating harms to communities when they do not “consider systemic influences on the program” (e.g., systemic racism; p. 380). We wanted to develop a tool that makes systems challenges even more visually linked to aspirations to hold storytellers accountable to exploring where their understanding of obstacles comes from.

From theory of change + evaluation data to one integrated tool

In our experience, even when logic models and theories of changes are useful and facilitated with equity principles, they’re often abandoned as soon as the evaluation gets started. While logic models can serve as “a programmatic tool… an evaluation tool… and a continuous feedback mechanism” (Zantal-Wiener & Horwood, 2010, p. 58), this use isn’t always clear, leading to logic models are often “static, simple, and predictable, while real life is dynamic, complicated, and somewhat unpredictable” (Hutchinson, 2014). We wanted to design a tool that clearly integrates the story (or theory) with data for three reasons. First, it becomes necessarily more of a living document where the story, or theory of change, can be tested against the data. Second, when people access evaluation findings to share the stories of their program, it will be automatically framed with communities and assets front and center. Last but not least, it simplifies design, evaluation, and communication processes so program staff can shift more resources to the actual program, and so that other community members have an easier access point to participate.

In thinking about how to make the data section as accessible as possible, we drew on the Results-Based Accountability (RBA) framework. This framework helps to make program evaluation more accessible by simplifying program evaluation to three questions: “How much did we do?," “How well did we do it?,” "Is anybody better off?” (Friedman, 2009, p. 82). This differs from the logic model by shifting from a focus on delivering outputs and outcomes to truly questioning how we can make a difference in people’s lives, which is aligned with the people-centered approach described above. We sought to incorporate simple, direct language into our developing tool.

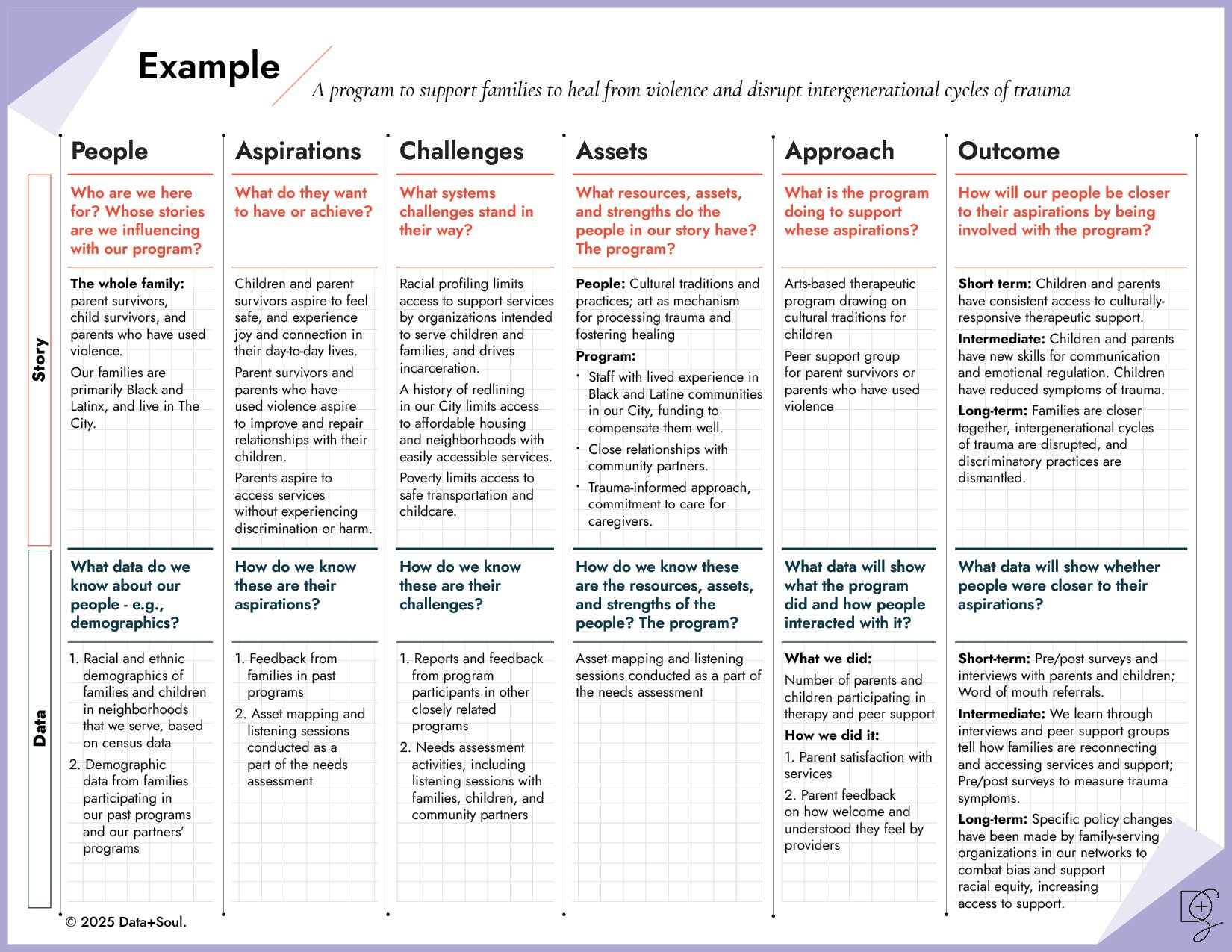

The Story+Data Map

Story+Data mapping is a light lift tool designed to support program and evaluation design in ways that embody the five shifts above. We start by defining the storytellers - making explicit the subjectivity of the process. The Story then places people at the center by asking: Who are we here for? What do they want to achieve? What systems challenges are standing in their way? How will we help them overcome these challenges, or intervene with systems directly, to help them achieve their aspirations? The Data half–mapped to the Story–is where we articulate how we know by asking: What data, evidence, and knowledge is our story built from? Where do we need to learn more, and from whom? To create an actionable plan to gather the data we need, the accompanying workbook includes an Evidence Gathering and Action Planning section.

Story+Data Map

We encourage Storytellers to start by writing the Story together–drawing on the wisdom of multiple perspectives–and then working through the Data. Once grounded in the Story, it’s important to acknowledge how the Storytellers know what they know about the people already (i.e., where does the evidence from the Story come from?) and identify opportunities to learn more that can help them refine the Story. In this way, the Data section helps Storytellers look back at their existing knowledge, unearth and test their assumptions about what they know, and identify gaps in their knowledge. This includes defining whose perspective(s) the knowledge is gathered from - an important aspect of shifting from single narratives to those grounded in multiple truths. The Data section is also a space to articulate how Storytellers will document what they’ve done and how they’ll know if it’s helped people move towards their aspirations.

Story+Data Map with a program example

Conclusion

The Story+Data Map is grounded in a lineage of equitable evaluation, storytelling with/as data, and other methods that use data and framing to push forward our work on critical issues of equity and social justice. We built a new tool for program design and evaluation that unifies five necessary shifts from the logic model:

From logic to storytelling

From centering programs to centering people

From people’s needs to aspirations and assets

From naming context to positioning systems challenges

From theory of change + evaluation data to one integrated tool

These shifts resulted in a one-page tool that is designed to intertwine the narratives and the data, knowledge, and evidence that have shaped it or are needed to shape the story, explicitly stated to be created by the specific set of storytellers who developed it.

Because the tool was initially designed as a logic model alternative, we wanted to go through the basis of our thinking and celebrate the people and theories that have shaped our approach. However, the Story+Data Map has already shown to be more flexible and powerful than we originally intended. Team members have used it in designing programs, coaching others in evaluation, and helping teams bring in community perspectives about the current landscape. We have created a workbook so that anyone can pick up the tool and facilitate a process of storytelling with it. We also offer a set of ideas about how the tool can be used even more expansively - though we’re sure you’ll think of even more imaginative ways to use it than we can. If you do, drop us a note. We'd love to hear about it.

We are publishing this paper in a time of deep uncertainty in the world, one where communities, programs, staff, and leaders need to re-envision the presumed narratives of change, what we think of as credible evidence, and how we work together. Amidst this turmoil we see clearly aspirations for a world of justice; strengths of creativity, determination, and community; and needed analyses of systems challenges in order to move with our communities closer to our collective dreams. We hope this tool will be a small but valuable piece in these efforts.

Acknowledgements

This paper was written by Susan Putnins, Chantal Hoff, and Elizabeth Whitcher. Each of these authors contributed significantly to outlining, drafting, and revising the paper. Min Ma advised on framing and offered feedback on drafts. Our teammates at Data+Soul Research, as well as the clients we work with, generously shared their experiences using the tool with us and offered us invaluable feedback that sharpened our thinking.

Susan originally designed the Story+Data Map with feedback from and thought partnership with Min and Diana Perez Cordova. Over the years, many hands have helped shape and grow this tool and how we use it, among them: Evan Kuras, Outlaw, Kayla Benitez Alvarez, Bobbie D. Norman, Hassan Lubega, Red Fong, Chantal Hoff, Elizabeth Whitcher, Tien Ung, and each of the changemakers, community members, storytellers, evidence builders, and who we have had the opportunity to share the Story+Data Map practice with through our work. These conversations refined the tool and expanded our thinking about what this tool is and what it can be.

Related Resources

-

The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2004). Theory of change: A practical tool for action, results and learning. Baltimore, MD. Retrieved from https://www.aecf.org/resources/theory-of-change

Benjamin, R. (2024). Imagination: A manifesto. WW Norton & Company.

Clarke, G. S., Douglas, E. B., House, M. J., Hudgins, K. E., Campos, S., & Vaughn, E. E. (2022). Empowering Indigenous communities through a participatory, culturally responsive evaluation of a federal program for older Americans. American Journal of Evaluation, 43(4),484-503.

Chilla, M. (2024, June 14). The American songbook’s “I want” songs. Indiana Public Media Afterglow. https://indianapublicmedia.org/afterglow/the-american-songbooks-i-want-songs.php

Dart, J., & Gates, E. (2024). Incorporating futures thinking into the theory of change: Case and lessons learned from a social enterprise intermediary in Australia. New Directions for Evaluation, 2024(182), 45-62.

D'ignazio, C., & Klein, L. F. (2023). Data feminism. MIT press.

Equitable Evaluation Initiative. (2023). Equitable Evaluation Framework™ (EEF).https://www.equitableeval.org/framework

Equitable Evaluation Initiative. (2024). Practice. Equitable Evaluation Initiative. https://www.equitableeval.org/practice

Evergreen, S., Sanjines, S., Emery, A. K., Marsack, J. R. (n.d.). Data visualization checklist. Evergreen Data. https://stephanieevergreen.com/data-visualization-checklist/

Friedman, M. (2009). Trying hard is not good enough: How to produce measurable improvements for customers and communities. BookSurge Publishing.

Gardner, F. (2000). Design evaluation: Illuminating social work practice for better outcomes. Social Work, 45(2), 176-182.

Hood, S., Hopson, R. K., & Kirkhart, K. E. (2015). Culturally responsive evaluation. Handbook of practical program evaluation, 281-317.

Hutchinson, K. (2014, January 12). Are logic models passé? American Evaluation Association AEA365. https://aea365.org/blog/kylie-hutchinson-on-are-logic-models-passe/

Joseph, A. L., Monkman, H., & Kushniruk, A. W. (2022). An evaluation guide and decision support tool for journey maps in healthcare and beyond. In Advances in Informatics, Management and Technology in Healthcare (pp. 171-174). IOS Press.

Kidder, D. P., Fierro, L. A., Luna, E., Salvaggio, H., McWhorter, A., Bowen, S., Murphy-Hoefer, R., Thigpen, S., Alexander, D., Armstead, T. L., August, E., Bruce, D., Clarke, S. N., Davis, C., Downes, A., Gill, S., House, L. D., Kerzner, M., Kun, K., CDC Evaluation Framework Work Group (2024). CDC program evaluation framework, 2024. MMWR. Recommendations and Reports, 73.

Knaflic, C. N. (2020, May 21). The structure(s) of story. Storytelling with Data. https://www.storytellingwithdata.com/blog/2020/5/21/the-structures-of-story

Marshall, T., & Shillingford, A. (2017, January 3). Intelligent mischief: Contending for dreamspace. Medium. https://medium.com/indian-thoughts/culture-and-our-salvation-b152b04626c8

Meyer, M. L., Louder, C. N., & Nicolas, G. (2022). Creating with, not for people: Theory of change and logic models for culturally responsive community-based intervention. American Journal of Evaluation, 43(3), 378-393.

Nasir, N. (2021, September 30). Edmund W. Gordon Senior Distinguished Lecture and Luncheon [Keynote address]. Center for Culturally-Responsive Evaluation and Assessment Conference, Chicago, IL. https://crea.education.illinois.edu/conferences/past-conferences/sixth-international-conference/keynote-speakers

Roman, C. G., Talley, A., Sierka, C., George, K., Water, K. V. D., & Aye, J. (2025). Collaborative creation of a logic model and performance metrics for evaluating a violence reduction program. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 24, 16094069251319866.

Shorters, T. (2019). The power of perception: A beginner’s guide to asset-Framing: Defining people by their aspirations and contributions instead of their deficits. ChangeAgent. https://changeagent2019.comnetwork.org/2019/the-power-of-perception/

W. K. Kellogg Foundation. (2004, January 1). Logic model development guide. W. K. Kellogg Foundation. https://wkkf.issuelab.org/resource/logic-model-development-guide.html

We All Count. (n.d.). The data equity framework. We All Count. https://weallcount.com/the-data-process/

Zantal‐Wiener, K., & Horwood, T. J. (2010). Logic modeling as a tool to prepare to evaluate disaster and emergency preparedness, response, and recovery in schools. New Directions for Evaluation, 2010(126), 51-64.